Filipino Sailors Dock in Mexico ... and Spark Tequila's Origins?

The Origins of Tequila: A Story of Cultural Exchange

Bottles of tequila have become a symbol of sophistication and luxury, especially in trendy bars across the globe. On social media platforms like Instagram, celebrity-backed tequila brands compete for attention, showcasing their unique flavors and heritage. Alongside this growing popularity, discussions about cultural appropriation and the sustainability of agave farming have gained traction. These conversations are taking place against the backdrop of booming tourism in Jalisco, the western Mexican state that is the heart of tequila production.

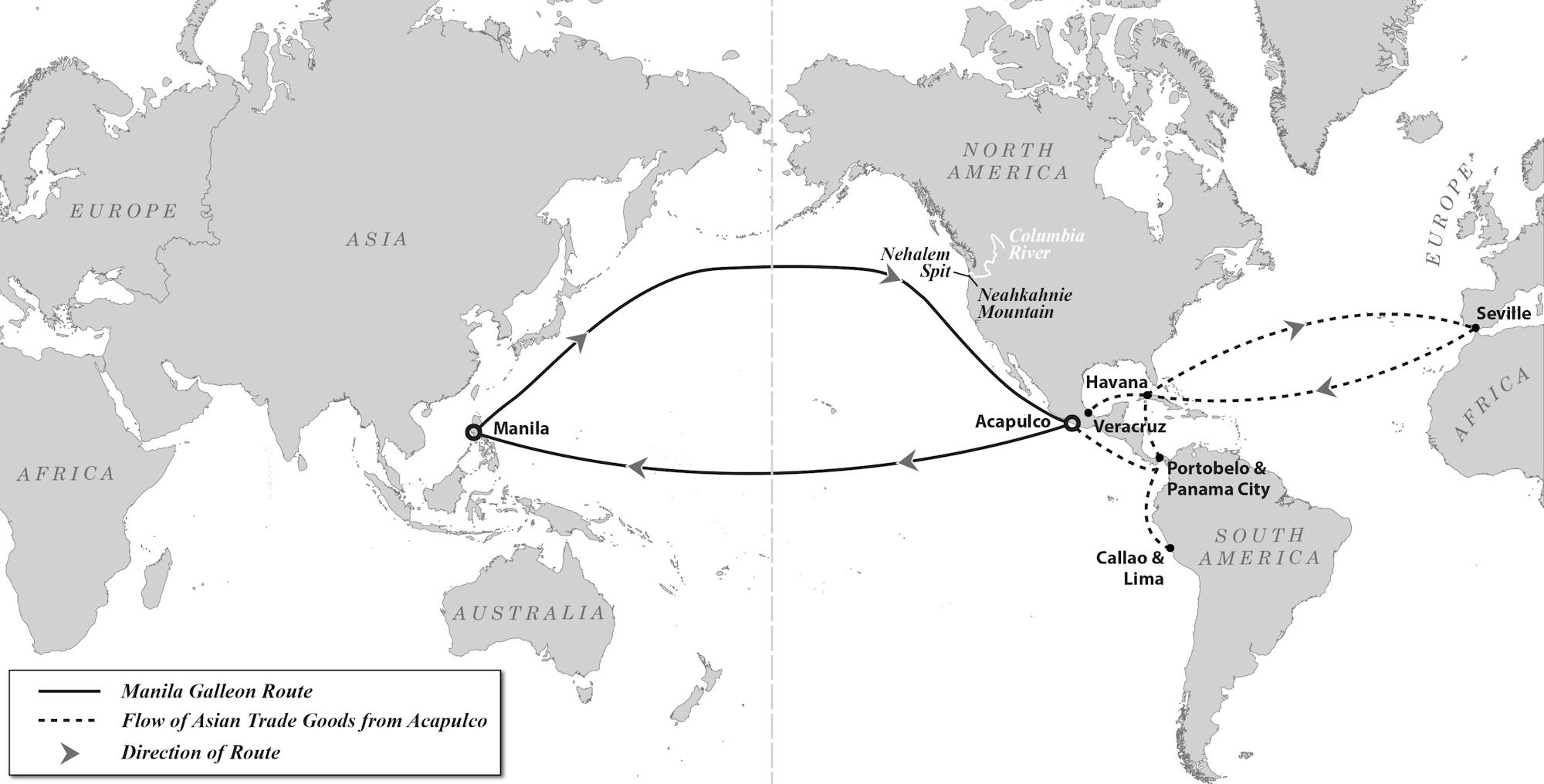

But behind the vibrant marketing and increasing demand lies a question that rarely gets asked: Where did the knowledge to distill agave come from in the first place? This question has sparked interest among scholars who are examining how Indigenous communities navigated colonialism and global trade networks. One area of focus is the Manila-Acapulco galleon trade route, which connected Asia and the Americas for over two centuries, from 1565 to 1815.

After Spain colonized the Philippines in 1565, Spanish galleons—massive sailing ships—traveled across the Pacific, carrying goods such as Chinese silk and Mexican silver. However, these vessels were not just transporters of goods; they also carried people, ideas, and technologies. Among these was the craft of distillation, a process that may have played a significant role in the development of distilled agave spirits like tequila.

Three Competing Theories on the Origins of Tequila

For centuries, the rise of tequila has been attributed to the Spanish. Following the conquest of Mexico in the 16th century, colonizers introduced alembic stills, which were based on Moorish and Arabic technology. These stills allowed for the transformation of fermented drinks into distilled spirits, marking a technological leap that enabled the creation of new beverages like tequila and mezcal.

Colonial records, including the "Relaciones Geográficas," describe how local Mesoamerican communities learned distillation from Spanish settlers. While this version is well-documented, it assumes that technology moved only one way—from Europe to the Americas. Another theory suggests that Mesoamerican communities already had some understanding of vapor condensation. Archaeological findings, such as ceramic vessels in western Mexico, indicate that Indigenous groups may have used methods similar to distillation before the arrival of Europeans.

A third perspective explores the potential influence of Filipino sailors and laborers. During the Manila-Acapulco galleon trade, thousands of Filipinos migrated to Mexico, particularly along the Pacific coast. In regions like Guerrero, Colima, and Jalisco, Filipino migrants introduced techniques for fermenting and distilling coconut sap into lambanog, a potent coconut-based spirit. The stills they used, sometimes called Mongolian stills, were built with clay and bamboo and included a condensation bowl. These designs closely resemble early Mexican agave distillation setups.

Beyond the Bottle: Cultural Legacies

The influence of Filipino culture extends far beyond the distilling process. In Colima and other Pacific port towns, traces of the Manila galleon trade can be seen in daily life, from kitchens to architecture. For example, the word “palapa,” used in Mexico and Central America to describe rustic thatched roofs, is the same term used in the Bicol Region of the Philippines for coconut fronds.

Filipino migrants also shared knowledge of boatbuilding, fermentation, and food preservation. Coconut vinegar, fish sauce, and palm sugar-based condiments became part of Mexican cuisine. One enduring legacy is tuba, a fermented coconut sap that remains popular in coastal areas of Guerrero, where Filipino sailors once settled. Tuba is sold in markets and along roadsides, often enjoyed as a refreshing drink or cooking ingredient.

Exchange was not one-sided. Filipino vessels carried corn, peanuts, sweet potatoes, and cacao back across the Pacific, influencing food in the Philippines. These exchanges took place under the shadow of colonialism and forced labor, but their legacies endure in language, taste, and even in the architecture of homes.

The Movement of Knowledge

Technical knowledge rarely travels through official channels alone. It moves with cooks in ship galleys, with carpenters below deck, and with laborers who settle in unfamiliar ports. Sometimes, it was a way to build a roof or preserve a flavor. Other times, it was a method for turning a fermented plant into a spirit that could last long voyages.

By the early 1600s, new types of distilled agave spirits were being made in Mexico. While tequila is unmistakably a product of Mexico, it is also a product of movement. Whether Filipino migrants directly introduced distillation methods or whether they emerged from a mix of Indigenous experimentation and European tools, every time you sip tequila, you’re tasting an echo of those long ocean crossings from many centuries ago.

Post a Comment for "Filipino Sailors Dock in Mexico ... and Spark Tequila's Origins?"

Post a Comment